Erla Þórdis Reynisdóttir

dairy farmer, ReykhólahreppurErla is a dairy farmer and enjoys

foraging for mushrooms, berries

and herbs in Breiðafjörður.

Erla looked concerned as she crouched down to inspect the udders of a dairy cow. The owner was doing the same, she was listening carefully to what Erla had to say. The dairy cow was not milking as much as it used to and it was getting unusually agitated. “Erla has a lot of experience. She always knows what to try.” The next time I ran into Erla was by a mountain. She was with her daughter and granddaughter. Each of them hauled buckets full of mushrooms and berries.

Erla has lived in Reykhólahreppur, a region in southeast Westfjords, for her whole life. She was raised in Gufudalur, a valley with waterfalls, dense birch shrubs, and colourful bogs.

“I did not think I was going to become a farmer because I had never enjoyed running after sheep up mountains and hills. But here, we got a cow farm, and we have been dairy farmers for 32 years. And this is just wonderful. Cows are calm and relaxing except when they are miserable. And sometimes they are.

When I was growing up [in Gufudalur], I thought there was no other countryside than my countryside. But [Mýratunga] is, naturally, well, the most beautiful in the world.”

Erla beams with satisfaction as we watch a white-tailed eagle spiraling slowly above her fields and her shores, in search for food when the tide is low and the sea recedes.

fig.1 Leccinum scabrum | Birch bolete (EN) | Kúalubbi (IS)

fig. 2 Boletus edulis | Porcino (EN) | Kóngssveppur (IS)

“Autumn is my time and I pick mushrooms, I pick berries and I am definitely what would have been called a forager. There are several kinds I collect, that are called Kúalubbi (fig. 1 Leccinum scabrum, birch bolete) and Kóngssveppur (fig. 2 Boletus edulis, porcino). There are a lot of them. Well, edible mushrooms in the Icelandic flora are just countless. But I like these two the best. They grow best in the heaths and mossy moorlands. So, yes, there is a lot of land for them here. Completely clean [land].”

We are now sitting by her kitchen table. She continues to work through a huge pile of bolete, peeling off the spongy hymenium from under the firm, fleshy cap.

“Usually I just pick it up, but if you cut it, leaving the ‘root,’ and then naturally it multiplies. The root gives the soil a fungal mass, so that it grows more. Since I picked this up this morning, I can go after about three, four days and then another such cap will be grown back. The mushroom season, in fact, begins in August. Then you have to go, because the fungus that has been growing for maybe half a month, became completely useless and wormy. This is why I have to go every few days, you always get new and beautiful mushrooms. It was not considered to be cool to eat mushrooms in Iceland… But this is delicious food.”

Erla also forages for berries: aðalbláber (fig. 3 Vaccinium myrtillus, European bilberry/whortleberry), aðalber*, and bláber (fig. 4 Vaccinium uliginosum, bog bilberry).

“It's all better with the aðalbláber, whether it's porridge or skyr or yoghurt… everything is better with berries.”

What she cannot find in the wild, she grows at home. “I’m so lucky to have a few chicken—so just like that—some chopped up mushrooms in a pan and four eggs on top, you bring food for two, three, four [people]…”

*We could not find the binomial nomenclature of this berry. It is commonly called svörtu (the black ones) and is considered as a variety of aðalbláber (Vaccinium myrtillus) by foragers.

With her vast knowledge of her land and its bounty, she enjoys being self-sufficient. “I like it a lot, yes, when you can sit at the table and all that’s on the table come from you and nature, yes. It's just the tip of the iceberg…”

fig. 3 Vaccinium myrtillus | European bilberry/whortleberry (EN) | Aðalbláber (IS)

fig. 4 Vaccinium uliginosum | bog bilberry (EN) | Bláber (IS)

fig. 5 Mentha aquatica | water mint (EN) | Mynta (IS)

fig. 6 Betula pubescens | birch (EN) | Birkir (IS)

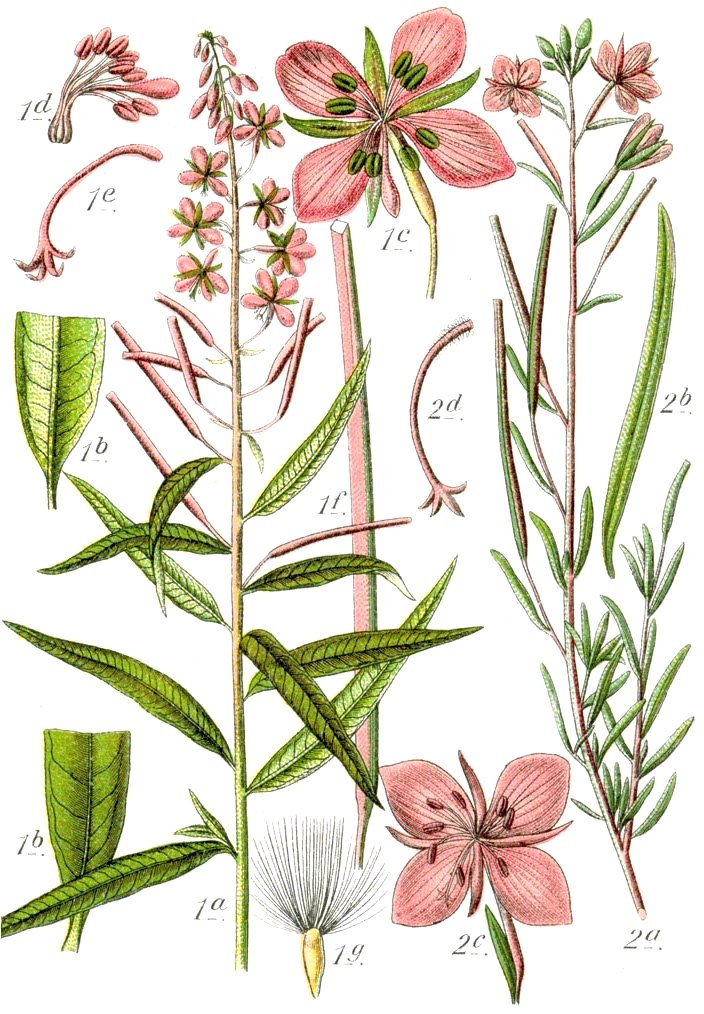

fig. 7 Chamerion angustifolium | Fireweed (EN) | Sigurskrúfur (IS)

fig. 8 Rumex spp. | dooryard dock (EN) | Njóli (IS)

fig. 9 Taraxacum officinale | dandelion (EN) | Fífill (IS)

fig. 10 Achillea millefolium | yarrow (EN) | Vallhumall (IS)

So I also harvest mynta (fig. 5 Mentha aquatica, water mint), birki (fig. 6 Betula pubescens, birch) and a plant called sigurskrúfur (fig. 7 Chamerion angustifolium, fireweed/willowherb) and is naturally the worst weed, but it is often weeds that are the best edible plant; njóli (fig. 8 Rumex longifolius, dooryard dock), fífill (fig. 9 Taraxacum officinale, dandelion)… And mint really improves the taste of all other teas, even if you have something like birki or vallhumall (fig. 10 Achillea millefolium, yarrow), which is not tasty in tea, then it will just be good with mint. I mix mint into all the tea I drink. This is just healthy. Then you just find out what makes you feel good. It is said that birch is good for sleep, like a ‘sleeping tea’… maríustakkur (fig. 11 Alchemilla vulgaris, lady’s mantle) for women in menopause, it is absolutely essential, for sweats and hot flashes. It fixes everything. It's like that, nature takes care of its own. It exists for us. I think so. Totally.”

“[It] is very calming. You are alone with yourself in nature that just, look, you stop hearing the traffic, which is only 300 meters next to you, you might hear if it's a truck, but you just completely forget. There is no need to think and if you need something to think about, it's just fine to go out and pick mushrooms. It's solves everyone's problem. This is just good.”

Without us noticing, Erla has pulled out all her ingredients, melted some butter in a pan and swiftly set the freshly cleaned mushroom slices in a sizzle.

“You only need two hours in the peat bog to fully charge your batteries. Just directly connect to nature.”

“This is the energy of nature… Well, I'm saying I'm a privileged person. Absolutely, look, it's such a privilege to have all this peace around here. I’m mostly picking [mushrooms and berries] alone. It's part of the luxury. Absolutely, no distractions. But luckily, my grandchildren and children find it fun, so, they definitely come with me when they are here [for a visit].”

The browned butter is gradually turning thick, saturated with the juice from the meaty mushrooms. She piles up the lightly caramelized, tender pieces with a spoonful of the luscious sauce in a dish and tossed more mushrooms into the pan.

In another pot, she swirls a generous slab of butter with a bouillon cube and a short pour of cream. A few handfuls of flour and incessant blending until the clumpy mixture becomes smooth and creamy, then in goes the sautéed mushrooms, au jus and fresh raw milk from her cows, poured from a bright pink jug.

“And yes, even though my grandchildren are only three years old, they think grandma's mushroom soup is amazing. So, yes, they just learn it right away. And rhubarb porridge with blueberries in it, frozen blueberries with cream, or ice cream, then [they’d ask] "Grandma, can you cook?" So I always have some frozen rhubarb, frozen blueberries and frozen mushrooms in the freezer. It's just a cycle. Like this, every year.”

Needless to say, we are all now very hungry. Together with her grandchildren, we sat around the kitchen table as the hot soup, fresh eggs, various kinds of vegetables from the garden, and apples and plums from the greenhouse are laid out one by one. I eat greedily.

“We have three children and, naturally, they have grown up and moved away [from the region]. I always say, well, of course we do not have our children. They choose the life [and] job that suit them. I'm certainly not the only farmer who faces the fact that there will be no generational change in farming here. So, you just have to start thinking about what you are going to do when you get older. I’m not quite there, but you have to start thinking about it. It's just a way of life, for sure. The only thing that can happen to you is that you grow old and disappear from here… then there is one thing that is certain in life, it ends somewhere.”

Erla seems to be at peace with the possibility that her dairy farm will close down when she quits farming. In 2018, she and her family built two log cabins near their home and started a guesthouse. It’s known for its coziness, wonderful host and incredible views.

“It's just so nice to be able to give others a chance to enjoy what we have here. I'm as happy as the dog when I have guests. And if the guests leave happy, then I'm ecstatic. I have been very lucky, the only problem I have with guests is that they do not leave on time.”

I am not surprised.

Article creditsInterview - Dagrún Ósk Jónsdóttir | Photos and article - Jamie Lee | Transcription - Hrafnhildur Anna Hannesdóttir

Illustrations from plantillustrations.org, biolib.de, Det Kgl. Bibliotek and Wikimedia Commons

Follow us on Facebook.