Ómar Smári Kristinsson

map-maker and bicycle tour book writerSmári draws maps, records landscapes and tours Iceland by bicycle.

On our drive up an old mountain gravel road around midnight, we saw a lone cyclist zig zagging upward against the gusty wind. When we caught up with him, we were not surprised to find out that it was Smári. He was on his way to survey the snow condition on the mountain pass in preparation for a bike race he helped to organise.

Anyone who has been to The Westfjords would have encountered a map or two by Ómar Smári Kristinsson (he goes by “Smári”). In his all hand-illustrated maps, he merges endearing functional, way-finding featuers with little detailed vignettes of daily lives around The Westfjords.

When we interviewed Nína, Smári would carry all our tea cups as we moved from room to room, then listen attentively on the side, with Jóna, their cat, snuggled next to him. He had a quiet, grounded and introspective energy. While we talked, he looked at us with his eyes wide-open and full of genuine curiosity.

Smári and Nína met in 1994 as art exchange students in Germany. Since then, they have been experimenting and building a fascinating life—from opening a “mountain mall” in the wilderness of Landmannalaugar, to furthering their art practices on an uninhabited island in The Westfjords during winters and to now, well-settled in Ísafjörður.

ST: Could you tell us where you are from and what you do?

SM: My name is Smári, Ómar Smári Kristinsson and I was born and raised in Rangárvallasýsla, moved to The Westfjords a quarter of a century ago and live there and will never move from there. Whether I call myself Ísfirðing, I do not know. There are different definitions of it. And it's probably best to just call me a draftsman, a map maker or an illustrator.

ST: Could you tell us about your background and what you studied?

SM: I was in Myndlista- og handíðaskóla Íslands (the Icelandic School of Art and Crafts), [in the] multi-media department. It had changed its name, it was once called the department of contemporary art […] Maybe it doesn't matter much now. What matters a lot is that I saw a post on a board somewhere in the school where an exchange program in Germany was offered and I was so lucky to choose Hanover as an exchange school. And there, I went to listen to what was being done in different departments, for example the sculpture department—luckily—because Nína was there—although she was not necessarily making a sculpture. And it paid off—there—I met her, Nínu minni (my Nína). And so, this hard world after school… it was not hard on us.. And now I have to admit, if I'm not getting off track, what was the question?

Smári's first map, drawn in 2000. He made it for Nína, so she could better understand the wind directions.

“So, yes, you could say that I have taken a detour from fishing to cartography. I haven't thought about it like that until now, but it's a bit simple, the world is a coherent whole.”

ST: Yes, I was asking what you studied… How did it develop that you went to work in Landmannalaugar?

SM: Poor Nína, when she arrived in Iceland from Germany, the first she knew of this country was the Highlands, where her lover fished in trout lakes. So she, the city girl, became a fisherwoman in the mountains under harsh and primitive living conditions. There were fishing lakes that were overfilled with small arctic char. The local fishing organization decided to try to fish out the small fish to make more living space. Some farmers of the area joined in. We would get nets and boats. The reward for that work was that we got to use the catch.

First it was sold in small batches to the finest hotels in Prague and Amsterdam. The travel group chefs here in Iceland huffed and puffed: "This is not even cat food in my house!"—just goes to show how powerful people's habits are. But the foreigners who came here, they naturally saw that there was only "créme de la créme" food, up in the mountains, straight from the waters. It was very popular. We were selling the fish out of the back of a small, old Land Rover. It was seen as "original" and exciting.

Smári and Nína selling arctic char they caught in the wild in Landmannalaugar, 1996.

Photo by Regína Hreinsdóttir.

And then we started to sell more products, since the hungry people—tourists and [with] no shops or anything—naturally flocked to us. And with Nína's arrival, we just started to have a fixed plan at Landmannalaugar.

Little by little, it turned into a shop. Even when we got there at six o'clock in the evening, lo and behold, all of a sudden there were queues of people, all wanting to buy fish. But people needed to be able to fry the fish from scratch, or have something to drink with it, or bread—some people can't live without bread—and we just met a demand. Before we knew it, we had a shop. First a little Land Rover and then a Hanomag and then a bus, and then two, and then, just a superpower—A "mountain mall."

The fish shop grew into a supply shop in a Hanover; from operating out of a Land Rover into a Hanover in 1998. Photo by Nína Ivanova and Smári Kristinsson.

Fjallabúð, “The Mountain Mall”, which also served as a tourist information centre, 2000.

Photo by Nína Ivanova and Smári Kristinsson.

And, of course, we also became a kind of information centre. Because these thousands of people who were coming out there into the desert were naturally grabbing everybody they could to get information. "Where is the pool? Where can I walk? What is the weather like? "When is the bus coming?" And so on and so forth. And we were answering several hundred questions a day, and usually the same questions.

I ended up drawing a map to answer these questions. By way of explanation, a map, and that map in fact, is now just our big cash cow, selling thousands of copies every year. So sometimes it pays to come up with ways to solve problems. So, yes, you could say that I have taken a detour from fishing to cartography. I haven't thought about it like that until now, but it's a bit simple, the world is a coherent whole.

ST: There seems to be a bit of a connection in all this you do, in work and hobbies and such…

It really does not matter what I do, bike books, travel companionship, drawing, hobbies, it somehow all flows into one whole before you know it. The world is like that. Maybe you experience more of it in places that are not big cities, for example, where the populations are smaller. It's just that all aspects of existence are interrelated. Life is whole.

ST: How did you arrive to live in Ísafjörður?

SM: It was so fortunate that just as we were getting bored with Germany and studying art, a place opened up on Æðey in Ísafjarðardjúp. We applied and got accepted. We ventured out to the island and learned a few things there, just by ourselves. There, we had enough time to do our craft and learn something new. Gradually it was heard in the community that there were people who knew something.

And when we then crawled ashore or started to take root here in Ísafjörður, people knew who we were and that helped us. We took on some work, a picture or a design or a website was needed, and so we just gradually got into it. Because the community is small and there is no oversupply of talented people. It is better to know a little about a lot than a lot about a little. In a small community, there will be a few of these versatile individuals.

In this tourist country, Iceland, there is often a lack of data to help tourists get directions and in my case, I started to draw maps—which suited me extremely well—because I have always really enjoyed maps. So, all of a sudden, I was able to get a job out of a hobby. Yes, I'm more of a draftsman than a visual artist, if I have to define what I do.

“It wasn't a bad thing at all to feel that you came and made a difference.”

ST: How is your experience with the community and working here?

SM: When we were on the island, we were kind of looking for a place to live because we wanted to have a home. We were nomads, people who moved from place to place. And of the places we did manage to explore, Ísafjörður was the most suitable. It's not a big city with its hustle and bustle, and it's not an island with just two people, but it's a decent-sized community that's still chock-full of culture and art, and it's enough that you can almost get over going to shows and concerts and this and that and get the inspiration we need, but not so much that you're overwhelmed with choices, not usually. Sometimes everything happens at the same time. Yes, this community is just very, very, very convenient for us and also very busy, the community needed us. It wasn't a bad thing at all to feel that you came and made a difference.

During a blizzard on Æðey, an island in Ísafjörðurdjúp where Nína and Smári spent seven winters as caretakers. Photo by Nína Ivanova.

ST: How has your time in Æðey shaped you, and what effect did it have?

SM: We just wanted to test how this new relationship of ours would be, with two of us alone in the world for many dark winter months. And it has now endured well enough for us to be there for seven winters and we were able to use that time well—both to develop our relationship as human beings and also to have time to learn something that our minds were made for. For example, we had never really seen a computer before, but now Nína is a computer genius. And the fact that I am still able to draw is also thanks to the time I had on the island to practice, to draw and draw. And read books, it is thanks to this time that I am not completely uneducated when it comes to literature. Now maybe I know something. I've never taken the time to study the literature of the world.

ST: You've also been publishing books about touring by bicycles, right?

SM: It's absolutely wonderful to travel on a bike, at a speed where you get to see some of the country and get to hear the sounds and smell the smells—to experience your surroundings. Something you can't do in a car or a plane. But maybe it's because I'm a country boy and I've always had to do something with a purpose or run an errand, that, in order to get around, or just wander around the country, that I had to do something about it.

So I started to write books, cycling books. Sharing my happiness with other people, pointing out fun places so more people can enjoy it than just me. It was very easy, it all came from the same place. I know how to take pictures and I know how to write nice texts, I know how to draw maps, of course, there are maps in the books. My wife is a graphic designer and knows how to get this material to the printer, and then we have a friend, Hallgrímur Sveinsson, who is a publisher in The Westfjords at Vestfirska forlagið. We did some work for him and he was more than willing to try to publish these books.

Then they were sold and they have stood the test of time and now I can even assume that I have an income from this… just live on what is fun to do. I think it's a luxury.

ST: Could you describe the process of creating maps for the areas that do not have maps, yet? From land to paper.

SM: Oh: yes. I just needed to listen to their wishes—what do you want to achieve with the map? Sometimes the customer wants the drawing to look as close to the place itself as possible. Starting such a career is practical here in the Westfjords, where there are mountains all over. I can just climb the nearest mountain to get the right viewpoint. Anyway, I'm always climbing mountains with the Travel Association (Ferðafélag Ísfirðinga), or by myself and in the case of work I'm practically doing the same. No need to invest in a plane or a drone with all those mountains.

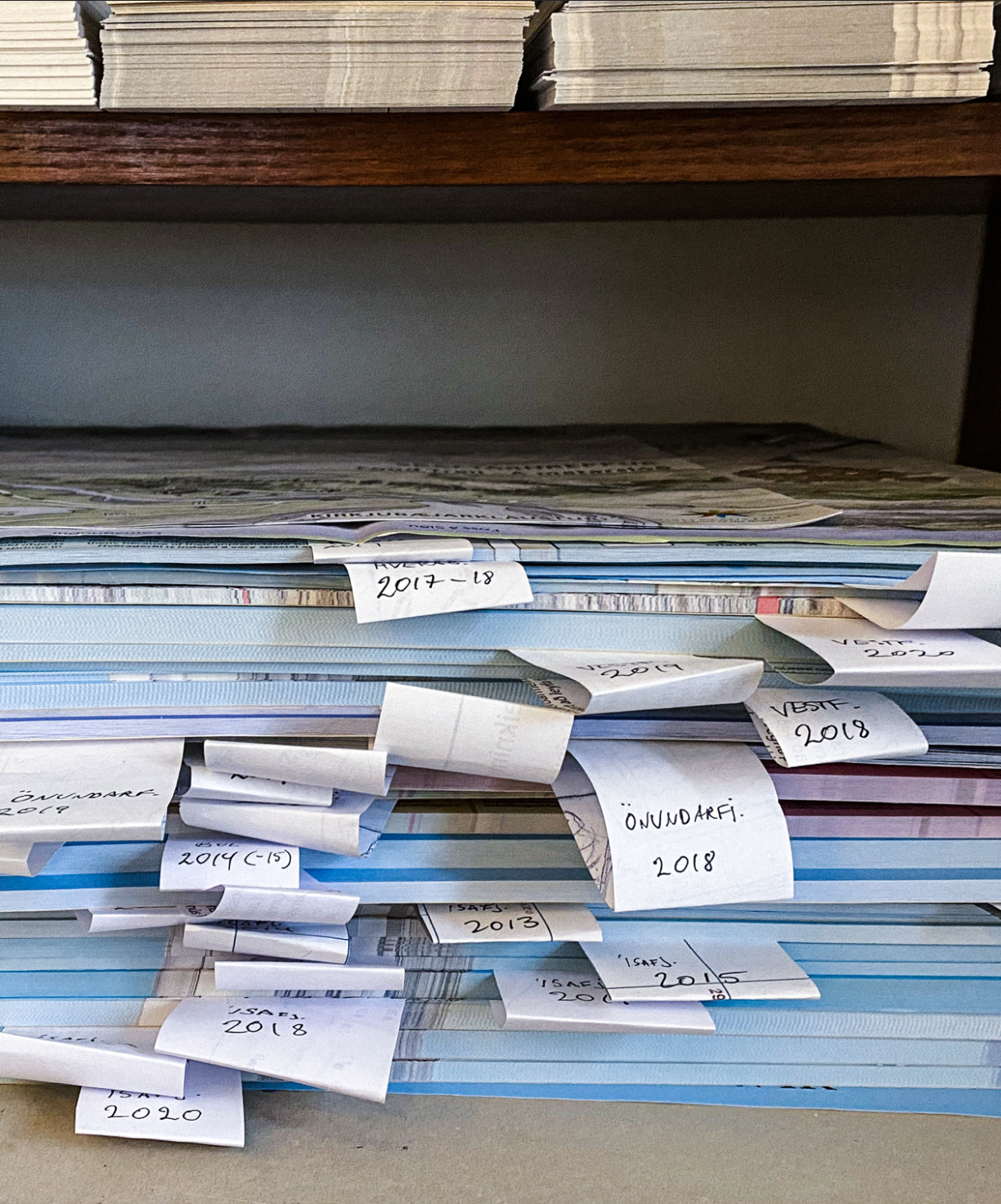

Some of the images collected by Smári to use as references to create a map of Ísafjörður.

But then there are others who just want to get the emphasis on something special; for tourism or some hot springs or some natural phenomenon. Then I highlight these things in particular. Then I get a poet's license. Although this may sound a bit strange, it's actually easier to create these maps where I can stretch and pull the subject. Pull some out and skip others. And to a certain extent, these are more fun subjects.

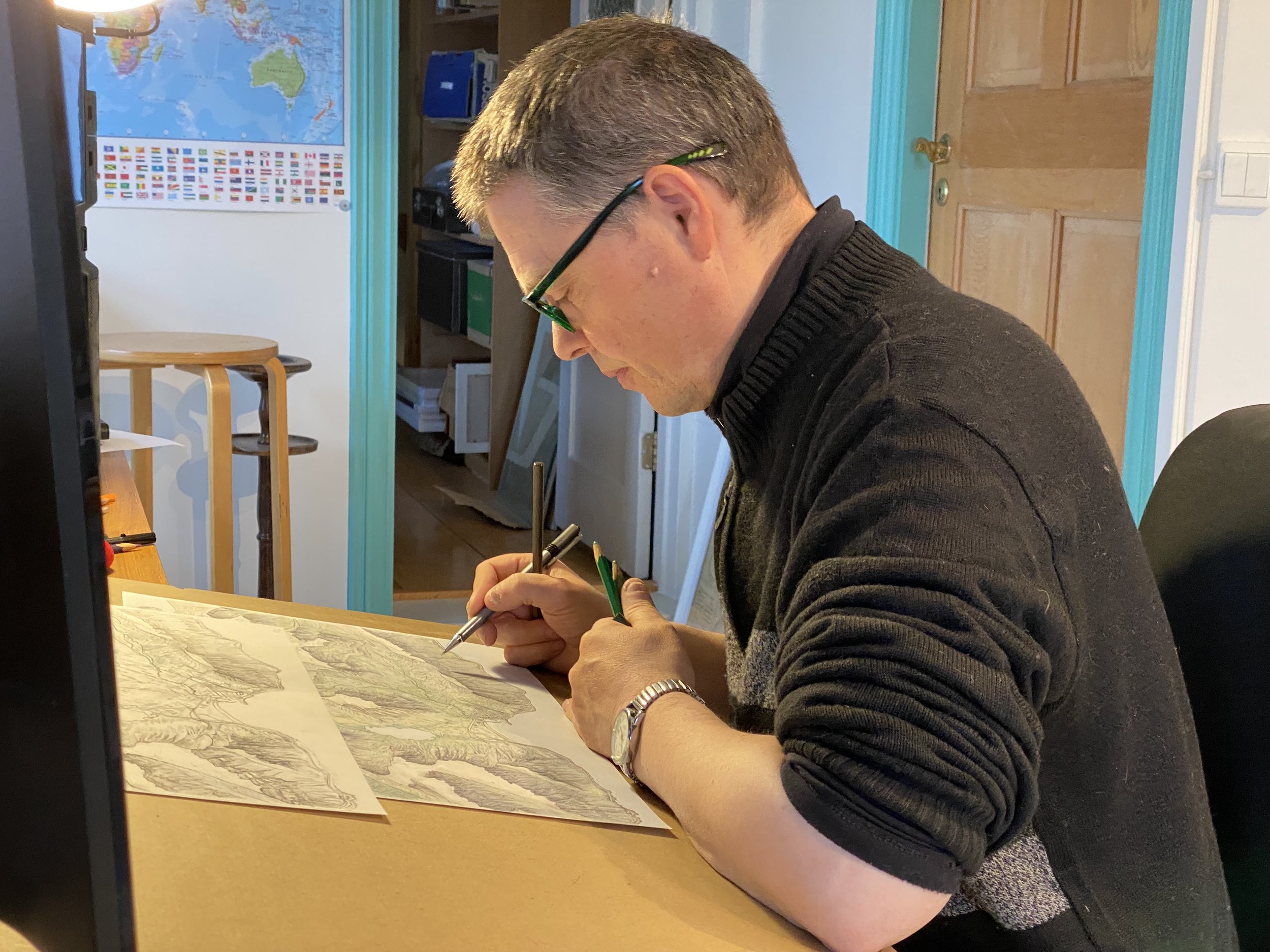

I don't have a photographic memory, so I take a lot of photos. Luckily, we live in an age where the internet exists and there are photos of almost everything. I can get both aerial photos and photos of streets and houses. So I sit here at this [computer] screen and collect [images]. Both my own pictures and others' and then I piece them together. I start by making a pencil drawing. It's almost like I'm shaping from clay, you see.

So when I'm happy with the result, I go over to the light table and turn it on and lay the sketch there and draw. Then usually I end up using pencils and colored pencils. These are the best tools for me to make a map like this, then I can make it fairly accurate and beautiful. When it's done, I scan it in and make corrections. And finally, this goes into the computer. Nína processes it so that it can be printed.

Þjóðgarðurinn Snæfellsjökull: Smári’s rendition of Snæfellsnes glacier national park with a healthy dose of “poet’s license”.

ST: There is so much information that can be included, how do you decide what not to include?

SM: Perhaps the biggest challenge in this drawing business and in these cycling books is choosing and rejecting. When I take some area that I need to draw and make a map, or describe in a bicycle book, I have to sift out what matters, or something that is beautiful or interesting or exciting.

It will be a personal choice, especially in the bike books. But often this is natural, well, just the customer, he says: "You have to have this and that and this and show this and that." And then sometimes there is no room for anything else.

So sometimes I get help with these decisions and sometimes I have to make them myself. And this is also often difficult when I'm drawing the maps that are supposed to show the areas as they are. Well, of course the map will never be exactly as the area is—I cannot draw every single curtain and every single cat or car wreck inside the backyard. Or yes, maybe somewhere one has to draw the line. Where do I pull them? I always have to make decisions. And maybe people do not necessarily want me to be drawing car wrecks in the backyard. So, yes, this is an endless headache, to choose and reject.

ST: Is it more challenging to do it by hand?

SM: It's much more of a challenge for me if I were to do it digitally, because I'm not from this century. I'm much more of a hands-on person, and it's much more instinctive for me, drawing. I am a painter. Yes, yes, forgive me, those of you who use a computer to draw—of course computers are wonderful drawing tools, you're just much better at it than I am. It’s just that I am a pencil kind of person.

Article creditsInterview - Steinunn Ása Sigurðardóttir | Article - Jamie Lee | Editing - Jamie Lee and Ó. Smári Kristinsson | Photo contributions as credited, additional from Jamie Lee

Follow us on Facebook